Lapis

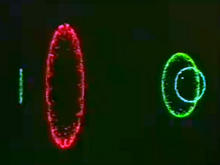

(1966)by James Whitney consists entirely of hundreds of constantly moving points of light and performs a transformation of positive and negative space, projected color and after-image, similarity and difference.

James Whitney's period of white wait (as the Chinese call such creative vacations) yielded a remarkable composure that manifested in the sense of balance of stasis and flow in his next masterpiece Lapis. James began preparing the intricate dot-pattern mandalas as he had those of Yantra, planning this film as Yantra II again. But after he had already designed the staggeringly complex sequence of subtle changes, and labored for some time on their hand execution John Whitney, Sr. offered to loan him a new computerized optical printing device he had developed - a pioneer motion control system prefiguring the slit-scan and other famous special effects creations of the later 60s. This equipment allowed James to complete Lapis in two years, which might have taken seven years by hand.

Consisting entirely of hundreds of constantly moving points of light, Lapis performs such marvelous transformations of positive and negative space, projected color and after-image, similarity and difference, that the viewer cannot help but contemplate the relationships of the unit to the whole, the individual consciousness to the cosmos, of space to time - and not a dry, forced meditation, but a supremely sensual, purely visual dialogue. Again, lapis, the Latin for stone, suggests the alchemical philosopher's stone, but no knowledge of hermetic doctrine is necessary to appreciate the wondrous display - the transmutation occurs directly in the viewer's mind.

Again, after Lapis, James made a white wait - this time throwing ceramics of great beauty and practicality - tea bowls, vases, and dishes that he and his friends could actually use in their homes.

(William Moritz: "Enlightenment", originally published in First Light, Robert Haller, Ed., New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1998)

Source: Center for Visual Music

The imagery is completely, conscientiously devoted to centric, circular patterns (like yantra-mandalas) and the film itself suggests a cyclical structure, beginning and ending with transparent white screen surface onto which the dots converge and from which they disperse, while vigorous flickers between pure red and green frames herald the opening union of particles into a pattern/illusion and the closing division of the pattern into parallel manifestations, implying, like the repeated Ouroboros logo, a continuing reoccurrence of the phenomenon. The red and greed colors (associated with beginning and ending in Alchemy, cf. Harry Smith's FILM No. 6) and the colors in general are precisely controlled as a factor of meaning in the film. Parallel rasters of dot patterns in varying colors are superimposed in many scenes to create, in a divisionist fashion, the effective or composite color sensation of the sequence. Other scenes unfold in related (complementary, approximate, etc.) pure colors which tease the mind/eye as to their identity, or in parallel patterns of complementary colors which refuse to blend (e.g. orange and green). However, in some scenes James even manages to superimpose red and green dots to yield the purplish puce color (associated with the union of positive/negative yin/yang to produce fresh vigor, royal power, occult wisdom, etc. in Hermetic thought) which appears otherwise as a pure hue in some other scenes. Another effective color frequently used in the film is the celestial blue, which is carefully planned to endure throughout a long sequence so that when it suddenly vanishes to black, the red/green Lotus wheel seems to float in a field of radiant (union/vigor) magenta because of afterimage from retinal exhaustion. This positive-negative color afterimage relates directly to the central theme of the film, in which most gestures and manifestations repeat in positive and negative states - e.g. the ring of dots converging on a white vs. later a black field; the dots forming a positive-space function by aligning in rows, chains or progressions vs. a negative-space pattern by enclosing and describing implied configurations.

(William Moritz, 1977, excerpt from manuscript in collections of Fischinger Archive and CVM. Manuscript written in English, Fall 1977, for translation and submission to Film als Film)

Source: Center for Visual Music

It’s difficult to see these films outside a special screening at a gallery or arts cinema. The Keith Griffiths documentary Abstract Cinema is an excellent introduction, including both Lapis and James Whitney’s Yantra among many other short works. However, this isn’t available to buy so viewing it means scouring TV schedules or waiting for some of these neglected works to turn up on YouTube. Gene Youngblood’s 1970 book Expanded Cinema discusses abstraction and the Whitneys and is available as a free PDF download here.

Source: John Coulthart