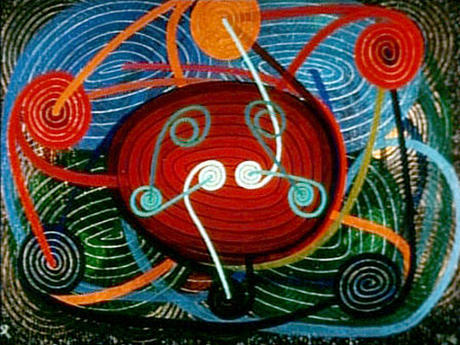

Motion Painting No. 1

(1947)by Oskar Fischinger put images in motion to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach's Brandenburg Concerto no. 3. It is a film of a painting (oil on acrylic glass); Fischinger filmed each brushstroke over the course of 9 months.

© Fischinger Trust/ Courtesy Center for Visual Music

According to William Moritz's comprehensive account of Fischinger's career ("The Films of Oskar Fischinger," Film Culture 58-59-60, 1974), Motion Painting No. 1 originated in 1934, when Oskar Fischinger first envisioned "making a grand and glorious film to be accompanied by Bach music." He returned to this project a decade later, with the support of a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, but after two years of false starts – "striking concepts [that] would have required a great deal of expensive help in production and probably expensive equipment," according to Moritz – "the grant film was still not really begun."

Baroness Hilla Rebay, then the curator of the Foundation, "became increasingly insistent since she had nothing to show for the foundation's investment after two years," Moritz writes. "Finally, in desperation, ... Fischinger dispensed with close synchronization to Bach, and resolved on using the one technique which he could relatively easily produce entirely by himself – he began painting as he usually did with a board fixed tight to a specially constructed easel with even lighting on each side to prevent reflection, and after each small brush stroke he rocked backward in a swivel chair and pulled a shoe string attached to the single-frame lever on a camera set up behind him focused exactly on the painting. ... Fischinger worked for several months on the first board, and when the paint grew too thick, he six times placed a plexiglas sheet over and continued, so that the finished film, eleven minutes long, constitutes one single take, one single flow of action."

Moritz writes that "Fischinger painted every day for over five months without being able to see how it was coming out on film, since he wanted to keep all the conditions, including film stock, absolutely consistent in order to avoid unexpected variations in quality of image."

As Moritz says, the film "shows a variety of styles from the soft, muted opening to the bold conclusion through a series of spontaneous changes prepared without any previous planning. All of the figures are drawn free-hand without aid of compasses or rulers or under-sketching, even the incredibly precise triangles of the middle section." The film actually seems to start rather slowly, with an overdose of Fischinger's trademark concentric circles (not really spirals, although he also uses those in other films), but then picks up speed. As Motion Painting No. 1 moves forward, it becomes much more inventive, and then astonishingly rich in its shapes and colors.

Motion Painting No. 1 is, as Moritz writes, a "formidable tour de force, astonishingly successful, and a fitting display of achievement for the last film of an acknowledged master."

The "last film," apart from a few TV commercials and fragments of unrealized projects, even though Fischinger lived for another twenty years, until January 31, 1967. As Moritz explains, the reasons were complex, but certainly Hilla Rebay's hostility to the finished film was an important factor. As baffling as it may seem, Rebay was outraged by "Fischinger's awful little spaghettis," and he received no more financial support from the Guggenheim Foundation. He could afford to have only a half dozen 16mm prints of Motion Painting No. 1 made, and they brought him little monetary return.

Source: Michael Barrier