Yantra

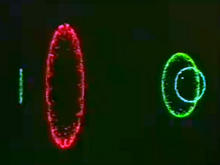

(1950-58)by James Whitney constructed by punching grid patterns in 5" x 7" cards with a pin, and then painting through these pinholes onto other 5" x 7" cards images of rich complexity and dynamism.

Yantra is a Sanskrit word meaning implement or machine. It can refer to a variety of systems, from simple meditational aids like mandalas, to the flux of cosmic energy that defines the essential flow of life and reality, or, in the specialized area of alchemy, to the vessel or grail in which the mystical transmutation is bred. But you do not need to know anything about these esoteric philosophies to see directly, and appreciate, the majestic visual transformations that happen in the film -- from gentle flickers between frames of pure white and black with no image at all, to seething masses of hundreds of points of light, each seeming to revolve in its own circuit. This range of quasi-musical variations of implosions and explosions, light and dark, hard-edged pure textures and thick, irregular, hand-wrought solarized textures induces a contemplation of the self and reality, identity and universality.

(William Moritz: "Enlightenment", originally published in First Light, Robert Haller, Ed., New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1998. Article courtesy: Center for Visual Music)

Source: Center for Visual Music

James worked on Yantra for about eight years (1950-58), meticulously painting the patterns of pin-point dots on paper cards, and hand developing and solarizing much of the footage. Although Lapis was executed in only three years (1963-6) with the aid of a computer, it can not be considered a computer-graphic per se, since the images were planned and hand-painted (exactly like those of Yantra, but on cel sheets) and the computer was merely used to ensure the accuracy of animation where hundreds of tiny dots must be precisely superimposed and moved in infinitesimally small graduations. And James seems to provide a Brechtian alienation from this astonishing technical perfection by including several momentary flaws, like a fleeting freeze in the action or a flash-frame from the beginning of a dissolve (again suggesting the cracks in raku ware).

(William Moritz, 1977, excerpt from manuscript in collections of Fischinger Archive and CVM. Manuscript written in English, Fall 1977, for translation and submission to Film als Film)

Source: Center for Visual Music

It’s difficult to see these films outside a special screening at a gallery or arts cinema. The Keith Griffiths documentary Abstract Cinema is an excellent introduction, including both Lapis and James Whitney’s Yantra among many other short works. However, this isn’t available to buy so viewing it means scouring TV schedules or waiting for some of these neglected works to turn up on YouTube. Gene Youngblood’s 1970 book Expanded Cinema discusses abstraction and the Whitneys and is available as a free PDF download here.

Source: John Coulthart