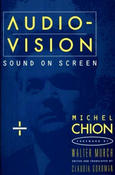

Sons et Lumières

(2004)– A History of Sound in the Art of the 20th Century (in French) by Marcella Lista and Sophie Duplaix published by the Centre Pompidou for the Paris exhibition in September 2004 until January 2005.

As a downbeat coda to Sons et Lumières (Sound and Light), an ambitious and exhaustive survey of relationships between visual and sonic thinking during the 20th-century, it tells you all you need to know about public attitudes to music that goes beyond the conventional ideas of narrative, tone and timbre. Such is the fate of sound as art (as opposed to pure music): generally unloved and unwanted, in comparison with contemporary plastic arts, where a Jackson Pollock or mid-1990s Brit Art retrospective can pull mass audiences.

Curated by the Pompidou’s Sophie Duplaix with the Louvre’s Marcella Lista, the show required a good three or four hours to absorb, with its bombardment of sensory and intellectual input, including painting, sound sculpture, sound/light automata, film and video, and room-size installations. The tangled and complex narrative of contemporary sonics was unpicked and arranged in three sections like separate essays – Correspondences (abstraction, colour music, animated light), Imprints (transformations, syntheses, traces) and Ruptures (chance, noise, silence) – which explored aural currents rippling through more established art narratives. (...)

Literal correspondence between image and sound came in a section devoted to prewar animation. Rudolf Pfenninger, a music scientist depicted in a nerdy pre-Nazi German newsreel, drew wave-forms and oscillation patterns onto the sound strip of film stock to generate pure tones, juddering noise and swooping vibrations when played through a projector. Animator Oskar Fischinger took up the baton once he had fled Hitler’s Germany for Hollywood to make animated symphonies for Walt Disney, including Fantasia (1940). (...) Postwar animations by Harry Smith, the Whitney brothers, Norman McLaren and Len Lye took this sense of four-dimensional concentration into more rarefied zones. (...)

The Ruptures section opened with a blast of the art of noise, with Luigi Russolo’s Futurist instruments, then jumped ahead to the tabula rasa of Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting (Two Panel) (1951) and John Cage’s original score for the 'silent' 4’33” (1952). Cage’s drawings on transparent plastic sheets, overlaid to produce the infinite performance permutations of Variations I (1958), Fontana Mix (1958–9) and other breakthrough works of the 1950s, attempted to reduce compositional consciousness to absolute zero. These graphic scores became Utopian maps, revealing free territories whose pathways were manifested in sound rather than ground.

(Rob Young)

Source: Frieze Magazine

ISBN-10: 2844262449

ISBN-13: 978-2844262448