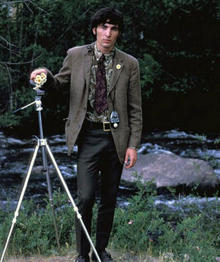

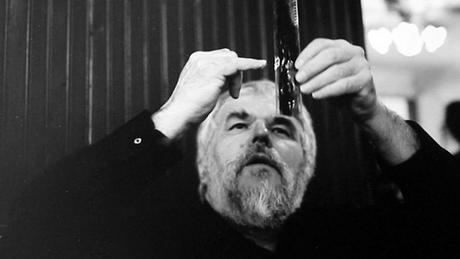

Stan Brakhage

(1933-2003) was an American non-narrative filmmaker who is considered to be one of the most important figures in 20th century experimental film. He frequently hand-painted the film or scratched the image directly into the film emulsion.

At some point in the future, when authoritative histories of twentieth century art begin to be written with the wise judgment that only distance from the present time can confer, I believe that Stan Brakhage will loom not only as one of the very greatest of filmmakers but as one of the major figures in all the arts. The sheer virtuosity of his work, the sensual beauty of his films' shapes and colors and textures, his creation of a unique and complex kind of visual music (most of his films are silent because the music comes from the screen), his appeal to the viewer as individual rather than as a member of a crowd, the ecstatic unpredictability of his spaces and rhythms, all assure the monumental importance of his close to 400 films, both individually and as a body of work.

This best known and most influential of all experimental or avant-garde filmmakers took light as his great subject, and his interest in light itself was tied to his interest in recovering that which he acknowledged no adult could ever recover, the pre-linguistic seeing of children ("How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of Green?" he famously asked), an interest which transmuted itself into a desire to free objects and light from structures based on language.

(Fred Camper "Stan Brakhage: A Brief Introduction" in the festival catalogue of the 5th Belo Horizonte International TIM Short Film Festival, 2003)

Source: Fred Camper's website

Over the course of five decades, Stan Brakhage created a large and diverse body of work, exploring a variety of formats, approaches and techniques that included handheld camerawork, painting directly onto celluloid, fast cutting, in-camera editing, scratching on film and the use of multiple exposures.

When Brakhage's early films had been exhibited in the 1950s, they had often been met with derision, but in the early 1960s Brakhage began to receive recognition in exhibitions and film publications, including Film Culture, which awarded several of his films, including The Dead, in 1962. The award statement, written by Jonas Mekas, a critic who would later become an influential experimental filmmaker in his own right, cited Brakhage for bringing to cinema "an intelligence and subtlety that is usually the province of the older arts."

From 1961 to 1964, Brakhage worked on a series of 5 films known as the Dog Star Man cycle. The Brakhages moved to Lump Gulch, Colorado in 1964, though Brakhage continued to make regular visits to New York. During one of those visits, the 16mm film equipment he had been using was stolen. Brakhage couldn't afford to replace it, instead opting to buy cheaper 8mm film equipment. He soon began working in the format, producing a 30-part cycle of 8mm films known as the Songs from 1964 to 1969. The Songs include one of Brakhage's most acclaimed films, 23rd Psalm Branch, a response to the Vietnam War and its presentation in the mass media.

Brakhage began teaching film history and aesthetics at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1969, commuting from his home in Colorado.

Brakhage explored further approaches to filmmaking in the 1970s. In 1971, he completed a set of three films inspired by public institutions in the city of Pittsburgh. These three films – Eyes, about the city police, Deus Ex, filmed in a hospital, and The Act of Seeing with One's Own Eyes, depicting autopsy – are collectively known as "The Pittsburgh Trilogy." In 1974, Brakhage made the feature-length Text of Light, consisting entirely of images of light refracted in a glass ashtray. In 1979, he experimented with Polavision, a format marketed by Polaroid, making about five 2 1/2 minute films. The whereabouts of these films are now unknown. He continued his visual explorations of landscape and the nature of light and thought process, and through the late 70's and early 80's produced filmic equivalents of what he termed "moving visual thinking" in several series of photographic abstractions known as the Roman, Arabic, and Egyptian series.

In 1979, Brakhage began teaching at the University of Colorado in Boulder. In 1986, Brakhage separated from Jane, and in 1989 he married his second wife, Marilyn. The two would have two children together. In the late 1980s, Brakhage returned to making sound films, with the four-part Faustfilm cycle, and also completed the hand-painted Dante Quartet.

Brakhage remained extremely productive through the last two decades of his life, sometimes working in collaboration with other filmmakers, including his University of Colorado colleague Phil Solomon. Several more sound films were completed, including Passage Through: A Ritual, edited to the music of Philip Corner, and Christ Mass Sex Dance and Ellipsis No. 5, both with music by James Tenney. He also produced the major meditations on childhood, adolescence, aging and mortality collectively known as the Vancouver Island Quartet, as well as numerous hand-painted works.

The last footage Brakhage shot has been made available under the title Work in Progress. At the time of his death, Brakhage was also working the Chinese Series, made by scratching directly on to film.

Source: Wikipedia